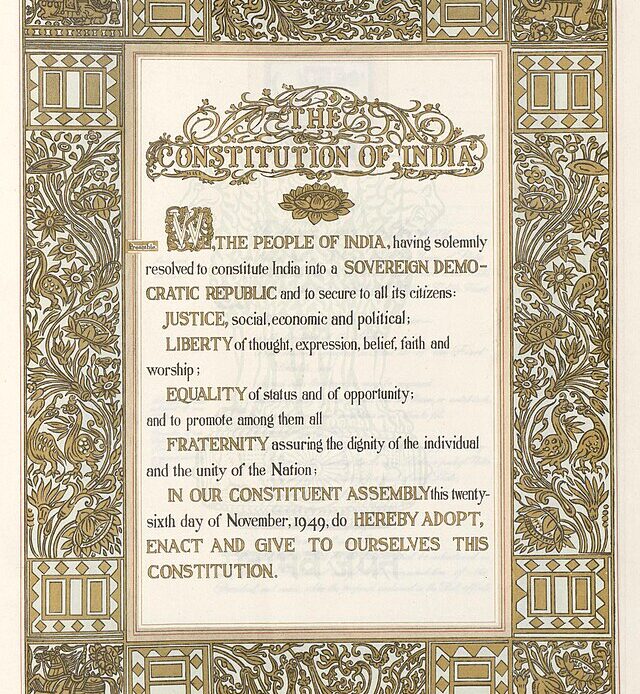

What is Basic Structure Doctrine: Constitution of India

Introduction

The Indian Constitution, serves as the supreme law of India. Among its many provisions, the doctrine of the “Basic Structure” holds a unique and paramount place. This doctrine ensures that certain fundamental aspects of the Constitution cannot be altered or destroyed by any parliamentary amendment, safeguarding the Constitution’s core values and principles. The Basic Structure doctrine has been a subject of extensive judicial interpretation and has played a crucial role in maintaining the constitutional balance between the Parliament’s power to amend the Constitution and the inviolable principles that form its foundation. It has been borrowed from German Constitution.

Table of Contents

Toggle

Origin and Evolution of the Basic Structure Doctrine

The concept of the Basic Structure of the Constitution was not explicitly mentioned in the original text of the Indian Constitution. It was developed through judicial interpretation, primarily by the Supreme Court of India.

Understanding the Basic Structure Doctrine

The basic structure doctrine is a judicial principle that restricts the Parliament of India from altering the “basic structure” or fundamental aspects of the Constitution through amendments. While the Constitution grants Parliament the authority to amend the Constitution under Article 368, this power is not absolute.

According to the doctrine, any amendment that seeks to change the essential features of the Constitution is subject to judicial review and can be declared unconstitutional.

The term “basic structure” is not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution; rather, it is a judicial innovation developed by the Supreme Court to maintain the integrity of the Constitution. This doctrine ensures that the foundational principles of the Constitution—such as the rule of law, separation of powers, secularism, federalism, and the protection of fundamental rights—remain inviolable, regardless of the political landscape.

Key Case Laws Leading to the Doctrine:

1. Shankari Prasad v. Union of India (1951):

In this case, the Supreme Court upheld the power of Parliament to amend any part of the Constitution, including Fundamental Rights, under Article 368.

2. Sajjan Singh v. State of Rajasthan (1965):

The court reaffirmed its earlier stance in Shankari Prasad, allowing Parliament the authority to amend the Constitution.

3. Golaknath v. State of Punjab (1967):

This case marked a significant shift, with the Supreme Court ruling that Parliament could not amend Fundamental Rights, effectively limiting its amending power. The court held that the Constitution was a permanent document and that any amendment affecting the Fundamental Rights would be void.

The Kesavananda Bharati Case: A Landmark Judgement

The basic structure doctrine was first articulated in the landmark case of Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala(1973). This case is one of the most significant in Indian legal history, not only for its impact on constitutional law but also for its long-lasting influence on the relationship between the judiciary and the legislature.

Background of the Case

The case began when Swami Kesavananda Bharati, the head of a religious mutt in Kerala, challenged the Kerala government’s attempt to acquire the mutt’s property under the Kerala Land Reforms Act, 1963. Bharati argued that the law violated his fundamental rights, particularly the right to property. His petition eventually led to a broader examination of Parliament’s power to amend the Constitution.

The Supreme Court’s Ruling

The Supreme Court, in a historic 7-6 decision, upheld the validity of the 24th Amendment, which affirmed Parliament’s power to amend any part of the Constitution, including fundamental rights. However, the Court simultaneously introduced the basic structure doctrine, stating that while Parliament could amend the Constitution, it could not alter its basic structure.

Justice H.R. Khanna, who played a pivotal role in the case, articulated that the Constitution’s basic structure includes essential elements such as the supremacy of the Constitution, the rule of law, the independence of the judiciary, and the principle of judicial review. These elements, according to the Court, are beyond the reach of Parliament’s amending power.

Impact of the Ruling

The Kesavananda Bharati case set a precedent that has shaped Indian constitutional law for decades. By asserting that certain parts of the Constitution are inviolable, the ruling established the judiciary as the ultimate guardian of the Constitution. This decision marked a turning point in the balance of power between the judiciary and the legislature, ensuring that the core values of the Constitution cannot be compromised by transient political majorities.

Subsequent Developments and Case Laws

Following the Kesavananda Bharati case, the basic structure doctrine was invoked and reaffirmed in several subsequent rulings by the Supreme Court, further solidifying its place in Indian constitutional law.

1. Indira Nehru Gandhi v. Raj Narain (1975):

This case arose out of the challenge to the election of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. The Supreme Court struck down Clause 4 of the 39th Amendment, which sought to place the election of the Prime Minister and Speaker of the Lok Sabha beyond judicial scrutiny. The Court held that the amendment violated the basic structure of the Constitution by compromising the principle of free and fair elections.

2. Minerva Mills Ltd. v. Union of India (1980):

In this case, the Supreme Court further expanded the basic structure doctrine by declaring that the power of judicial review is an integral part of the Constitution’s basic structure. The Court struck down certain clauses of the 42nd Amendment, which sought to curtail the power of judicial review and undermine the balance between the fundamental rights and directive principles.

3. Waman Rao v. Union of India (1981):

The Supreme Court upheld the validity of the basic structure doctrine, ruling that amendments made after the Kesavananda Bharati case would be subject to the basic structure test. This decision reinforced the doctrine’s applicability to future amendments, ensuring the continued protection of the Constitution’s core principles.

Comparative Perspective: Basic Structure Doctrine in Other Countries

The basic structure doctrine is unique to India and does not have an exact parallel in other constitutional democracies. However, similar concepts can be found in other countries, where courts have imposed limits on constitutional amendments to protect certain fundamental principles.

For example, in Germany, the Basic Law (Grundgesetz) explicitly restricts amendments that would alter the federal structure of the state, the rule of law, and the protection of human dignity. Similarly, in South Africa, the Constitutional Court has the authority to review constitutional amendments to ensure they do not violate the core principles of the Constitution.

These examples illustrate a global trend where constitutional courts play a crucial role in safeguarding the fundamental values of their respective constitutions, ensuring that democratic principles are preserved.

Conclusion

The basic structure doctrine is a testament to the resilience and adaptability of the Indian Constitution. By establishing an unassailable core within the Constitution, the Supreme Court has ensured that the foundational principles of Indian democracy remain intact, even in the face of changing political tides. The doctrine has not only shaped the trajectory of Indian constitutional law but also set an example for other democracies grappling with the challenge of balancing the power of constitutional amendments with the need to protect fundamental values.

As India continues to evolve as a constitutional democracy, the basic structure doctrine will undoubtedly remain a critical tool in preserving the integrity and spirit of the Constitution, ensuring that the ideals envisioned by the framers of the Constitution endure for generations to come.

Leave a Reply